The Henley Study

This room is a time capsule evoking the atmosphere of a typical late Victorian study representing the life and works of a most extraordinary man, William Cumming Henley (1860-1919). Henley, an ironmonger, embodied the Victorian thirst for knowledge and self-improvement. His restless curiosity drove him to a remarkable breadth of accomplishments: he was a talented artist and draughtsman, a keen amateur naturalist and microscopist, an avid reader and collector of books and paintings. All this was outside his working day of designing newly introduced flushing water closets for the gentry of the town.

Throughout his life Henley accumulated a substantial collection of items that had captured his intellectual interest. On his death the collection was bequeathed to the Borough (now Town) Council and the Henley Museum was established in Anzac Street, just round the corner. This museum had to close in 1976 and the collection then went into store, to be released on loan to Dartmouth Museum in 2005, when the Henley Study was built to display it.

In the cabinets around the study is an eclectic collection of birds’ eggs, shells, insects, fossils, minerals and other notable objects. Among these is a somewhat frightening shark’s jaw of a size easily able to take a human head. It is possible to see the ‘conveyor belt’ mechanism of the teeth with replacements lying flat in the jaw ready to spring up if outer ones are lost. Also of note is an example of the fabled nut known as the Coco de Mer or the Maldive Coconut. This first came to notice when husks were washed up on the beaches of the Maldive Islands. Early supposition about its origin was that it came from a mythical tree in the depths of the ocean but we now know that this largest nut in the plant kingdom, weighing up to 30kg, is from a small endangered community in the Seychelles Islands, now protected. The bi-lobed form often generated prurient comment among seafarers.

Coco de Mer – approximately 15 inches across

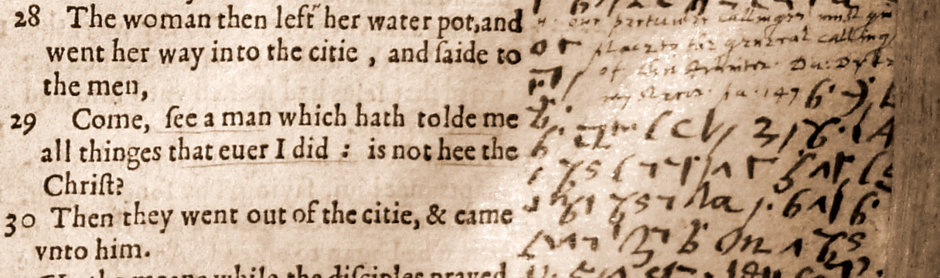

Of the very many books Henley collected, there are a number on display that are particularly interesting. One is a copy of the Geneva Bible, the first English bible to be mass produced with notes and numbered verses. This is the bible that the Mayflower Pilgrims would have taken to the New World in 1620. Henley’s copy is extensively annotated in the margins. But he used a primitive shorthand that has yet to be decoded.

Another book of interest is a copy of a volume of Raleigh’s ‘Historie of the World’ (1614). Raleigh, a one time favourite of Queen Elizabeth, fell out of favour with her and later with King James, and was incarcerated in the Tower of London. There he spent long years of his imprisonment on this ambitious project but with little hope of ever completing it, reflecting that he had started it too late: ‘the day of a tempestuous life drawn on the very evening ere I began,’ On display is Chapter XXVIII of Book 2 and he was still at 600BC! Raleigh’s writing was cut short on 29th October 1618, when he was beheaded.

The late Brian Langworthy – Curator

Henley – the artist

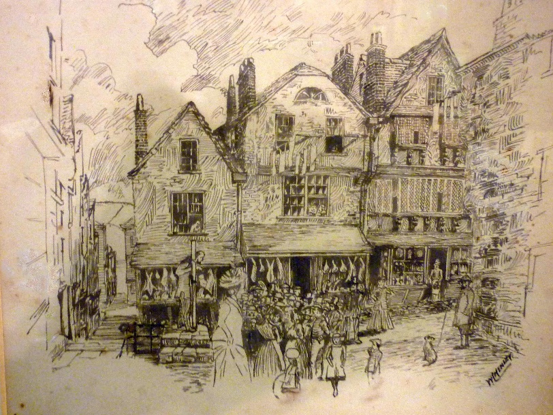

Henley, besides being an art collector, was himself an accomplished sketcher and watercolourist. His views of the town are now of particular interest, as it gives us a snapshot of Dartmouth as it was before the major road widening and demolition of the 19th and 20th Centuries. One of his pencil sketches, appreciated by local historians, is of the then commercial centre of the town at the junction of Higher Street and Smith Street. This was the place of public punishment and shows a miscreant in the pillory with a crowd looking on. The Museum holds the stocks that were also used but, regrettably, not the ducking stool.

Looking down Smith Street towards the river. The first house was demolished to widen the street. The third ‘Tudor House’ was severely damaged by fire in 2010 but the frontage was saved and the building reconstructed.

hands on discovery

Henley was a keen microscopist, finding the world of the very small both stimulating and soothing. He made his own instrument but was able to save enough for a professional microscope costing today’s equivalent of £2500. Both these are on view in a cabinet.

On the centre table of the room are microscopes and a collection of slides for anyone of any age to use. These include insects but not a flea. It is related that Henley, one day, wanted to view and draw a flea, so he asked a boy who came into his shop if he could procure one for the then princely sum of 3 pence for a good specimen. The news got out and soon there was a queue at his door of small boys from the poorer parts of the town, each with his flea and demanding 3D.

Henley’s self-made microscope shows knowledge of both metalworking and optics.